GHESKIO Construction Update

Photographs of the Gheskio Health Clinic, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, from September 2015. The main building is completed. The steel frames of the pavilions are erected and their completion awaits for further funding.

Photographs of the Gheskio Health Clinic, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, from September 2015. The main building is completed. The steel frames of the pavilions are erected and their completion awaits for further funding.

Construction Update | GHESKIO Family Health & Nutrition Center | PORT-AU-PRINCE, HAITI

Steel frame has been erected by Haitian work force, together with small American crew. Estimated Construction Completion: Fall 2014

GHESKIO & THE COMMUNITY SERVED:

The local community surrounding and served by GHESKIO consists of over 100,000 people living in slums and ‘tent cities’ on less than $1/day (as do ~56% of all Haitians). Malnutrition is widespread: Haiti’s malnutrition rates are among the world’s highest. One-third of Haitian children under age five are severely malnourished, and 40% suffer from anemia.

Since 1982, in partnership with the Haitian Government and Cornell University, GHESKIO has been offering free health care, including HIV counseling, AIDS care, prenatal care, and management of tuberculosis and sexually transmitted infections, and conducts research and training in HIV/AIDS and related diseases. In 2000, the Haitian government named GHESKIO a “Public Utility”, a designation reserved for institutions, which are ‘essential to welfare of the Haitian people’. In 2010, GHESKIO was awarded the Bill and Melinda Gates Award for Global Health for its outstanding contributions to the global health field.

Since the earthquake in January 2010 GHESKIO has expanded its mission to also provide comprehensive health care and community services, including reproductive health care, clean water, sanitation, food, security, education and social services.

GHESKIO FAMILY HEALTH & NUTRITION CENTER:

The new Family Health & Nutrition Center, designed by NYC-based firm Tonetti Associates Architects, represents GHESKIO’s new, comprehensive approach to nutrition, clinical care and community development. The design takes into account the many challenges of building in Haiti, while reflecting the purpose and program of the facility. Tonetti Associates Architects investigated sustainable and durable structural systems that can be constructed by a relatively unskilled local work force and chose cold rolled steel frame, which is lighter and resists lateral loads better than concrete frames. Steel frame has been fabricated by Blue Sky Building Systems (http://blueskybuildingsystems.com).

Funding: MAC Aids Foundation grant and private donations. Fundraising still in process to complete construction. Weill Cornell Medical College, a 501(c)(3) organization and partner of GHESKIO since its inception, receives donations.

www.weill.cornell.edu/globalhealth

Our architectural design approach is rooted in profound respect for the natural environment and the efficient use of resources. TAA designed the first passive solar building, commissioned by the State of New York in 1982 – the Mid Hudson Activity Center. We have designed numerous additional sustainable buildings, such as the Hackettstown Fish Hatchery and the Mars Education Center at Fort Ticonderoga (LEED accredited). Our staff includes LEED certified professionals.

Taking the ferry to Governors Island, view of Brooklyn.

Fort Jay with view of Manhattan.

TAA just completed full interior and exterior modernization of PS 132 in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, winning the approval of the New York State Historic Preservation Office. In this major renovation we restored the building facade, designed a playground, addressed curriculum concerns and security issues. With new roof insulation and total window replacement, we are anticipating that the energy use in the building will be reduced by 30%. — with Andrew Wright at PS132, Brooklyn.

TAA just completed full interior and exterior modernization of PS 132 in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, winning the approval of the New York State Historic Preservation Office. In this major renovation we restored the building facade, designed a playground, addressed curriculum concerns and security issues. With new roof insulation and total window replacement, we are anticipating that the energy use in the building will be reduced by 30%. — with Andrew Wright at PS132, Brooklyn.

Beyond South Florida, Clemence has registered relevant modern and contemporary buildings all over the world, from the geometric lines of Mies van der Rohe to the expressionistic abstraction of Frank Gehry, all caught in film, making the often silent art of architecture properly heard. View here.

Challenges of Housing Production for the Poorest in the Developing World

Report on the 300 Dollar House Workshop, January 25-28 2012 at Dartmouth College

“The Three Hundred Dollar House, you mean three hundred per square foot?” A friend’s incredulity summarizes the responses I heard to the title of a workshop at Dartmouth College. He and I worked together on a project costing multiples of 300 dollars per square foot, his career is in construction, and he knows the price of a pound of nails. The thought of building a house for $300, even at the most minimal standards, seemed an impossibility.

The initial idea of the THDH* was the brain child of Vijay Govindarajan, a professor at the Tuck School of Management at Dartmouth College and Christian Sarkar, referred to as the disruptive fellow in the back. They conceived of the “brand” to bring attention to the issues of housing for the very poorest in the developing world. By provocatively setting the price that low they hoped to push architects, engineers, planners and financiers to explore innovative designs and economic models. They organized an online international competition to initiate the process. Coincidentally the competition drew 300 hundred entries.

From these entries a jury selected six finalists. Many of the finalists were able to attend a workshop hosted by Dartmouth in Hanover in January 2012. The workshop’s goals were to capture the energy sparked by the competition and to explore the steps necessary to create something that would cast a shadow. The workshop, organized by Jack Wilson of the Studio Arts Department, focused on Haiti because of Dartmouth’s connections to the country and its pressing needs.

In addition to the finalists, Dartmouth students and faculty from the engineering and business school, participants from Haitian groups and a handful of engineers and architect were invited. I was included because of my familiarity with designing and building in Haiti. For three intense days the participants wrestled with the issues of urban and rural housing, community development and financial models.

Two Haitian communities, one rural and one urban, were the focus for the workshop. Strong organizations within both communities had originally provided medical services and then branched into social services. Fond des Blancs, a stable rural community relatively untouched by the January 2010 earthquake, benefited from the St. Boniface Haiti Foundation. Cite de Dieu is an urban “slum” in Port-au-Prince. After the earthquake GHESKIO Center, a nearby clinic, filled a vacuum left by a weak and overwhelmed city government by providing not only community medical services but also other significant municipal functions.

During the workshop it fell to me to wear an unfamiliar hat. Instead of my architect’s role Jack asked me to lead the group on community development and infrastructure. We were charged with addressing eight areas:

This formidable list was initially an obstacle. We could not find the key to unlock the process of thinking about the issues of Fond des Blancs and Cite de Dieu. We had too many avenues and too little time and data. It was Jean St Denis, a community organizer from Fond des Blancs, who set us on the right track. He gently repeated until we listened “employment is the key”. He pointed out that even if it was possible to build a three hundred dollar house it still had no viability unless a person could afford it.

Cite de Dieux, Photo

With that insight we looked closely at the issues that inhibited the economic and employment picture of Font des Blancs. We acknowledged that as an island nation with minimal natural resources Haiti’s economic base will eventually lie in exporting their unique products overseas, but assuming that walking must come before running we decided to focus on the local market in town. A list of items available there was developed. The question was raised why there was no fish available at the market even though the town was only 20 kilometers from a coastal fishing village. Jean St. Denis concluded that the issues were not so much physically imposed as the result of culture and customs. He promised to return to Fond des Blancs and institute a motor bike delivery service for fresh fish preserved in ice.

We recognized that many of the issues of poor employment options were not so easily addressed and that it was presumptuous of us to propose solutions from Hanover for Haiti. The general consensus of the workshop participants living in Haiti was that the issue was not a lack of financial resources. There are non-governmental organizations and international governmental agencies looking for viable projects to support and fund. Haitian groups with plans and community backing were in demand. To help Fond des Blancs gain visibility we suggested that a formation of a community development council was a start. The council of the leaders and change agents of the community would analyze in a more thoughtful and through way the steps that we had started.

To that end we created a Facebook page Fond des Blancs as a simple step to help increase the visibility of the community. Please feel free to add your comments there.

Unfortunately we were forced to leave the issues of Cite de Dieu for another time or another group. Besides not having enough time we realized that the urban context had different circumstances. In particularly it is a more fluid and open system.

So if you have read this far and you still do not have the answer to the question “can you build a house for 300 dollars”, the answer is no, at least not in Haiti at the present moment. There does not seem to be a silver bullet for the issues of housing costs, much less the expensive infrastructure. Industrial housing solution is effective in areas with good transportation access and high site labor costs. Lowered costs generally only apply when the scale of production is hundreds, not tens, such as in Levittown, NY after WWII. Traditional materials and forms frequently effectively meet the needs of people who for financial reasons must build their housing in stages. Framing systems which over time may prove more cost-effective, but their introduction into the Haitian market is at a nascent stage.

Immediately after the earthquake there was a plethora of proposals for inexpensive relief housing from designers, architects and engineers of the developed world. Many of these proposals had little relation to Haitian needs and housing expectations, nor to the climate and construction realities of the country. Thankfully most proposals did not get beyond the talking stage.

At the Dartmouth workshop the two (rural & urban) housing groups had members who understood the issues relevant to Haiti much more clearly. The groups developed designs based on habitable standards and traditional materials and layout. They responded to the difficulties of building in Cite de Dieu, with the existing poor soil conditions and flooding. In Fond des Blancs the traditional form of front porch, sleeping quarters and rear yard for cooking were respected.

However, in both locations the costs were in the thousands of dollars, not in the hundreds – even when pared down to the “basic starter unit”. So if the number was wrong, does that invalidate the process? Without that number or another like it, the workshop would not have gotten off the ground. If you can harness the energy of the workshop into a prototype, if a student’s career takes on an added dimension, if the arrival of fresh fish in Fond des Blancs triggers the birth of a stronger market, then the workshop was a success.

We have successfully turned over all construction documents to the Haitian construction manager. Haitian contractors are currently bidding on the project. We are investigating stabilized earth as building materials.

By Andrew Wright

Thanks to a Siren call at a flea market, I recently found myself with several dozen issues of ‘Pencil Points, A Journal of the Drafting Room’ dating from the nineteen thirties and forties. ‘Pencil Points’, as its subtitle indicates, focused on the toilers of the architectural firms. Its readers had aspirations no higher than the drafting room. They wore green eye visors, celluloid cuffs and cotton jackets. Along with Microtomic Van Dyke drawing pencils, this group – for whom drafting was their true job description – has largely disappeared, to be replaced by graduates of architectural school who hope to quickly work their way out of the title. ‘Pencil Points’ also has disappeared. It merged with ‘Progressive Architecture’ in the mid forties, and with the merge, the magazine gradually lost its drafting room orientation. ‘Progressive Architecture’ became the most influential of the “glossy” main stream architectural magazines but ceased publication in December 1995.

Both the articles and the advertisements of these early issues are interesting as paleographic markers defining the state of the profession in the 1930s and illustrating the evolution of our field in the intervening seven decades.

The articles in the issues from the early 1930’s do not directly acknowledge the economic maelstrom that the profession was facing. The lead-off article of the October 1932 issue was entitled “Architecture, Art or Science?” The author, Louis La Baume, grappled with the role of art and science in architecture and wisely decided that this role could not be defined in words. This article was followed by an illustrated monograph on “Early Interior Doorways of New England” and another illustrating the comparative details of dormers in traditional residences.

Though not stated, the profession’s turmoil can be inferred. The exquisitely drafted dormer drawings were prepared by the “New York Architects’ Emergency Unemployment Committee”, whose descendent seems to be the “Not Business as Usual” committee of the New York City Chapter of the AIA formed in December 2008. The NBAU web site makes clear the challenges the profession faces: “The economic downturn has had a significant effect on the design community in New York City. The NBAU program focuses on what design professionals need to know and do for themselves and their firms to thrive”.

Another example of the hard times in the 1930s is the employment listings at the back of the October 1932 issue. There are no listings for help wanted. The ads for the positions wanted include such plaintive supplications as “Willing to take any position and salary offered” and “will work for $35.00 per week anywhere”. These sound agonizingly familiar to anyone looking for work today.

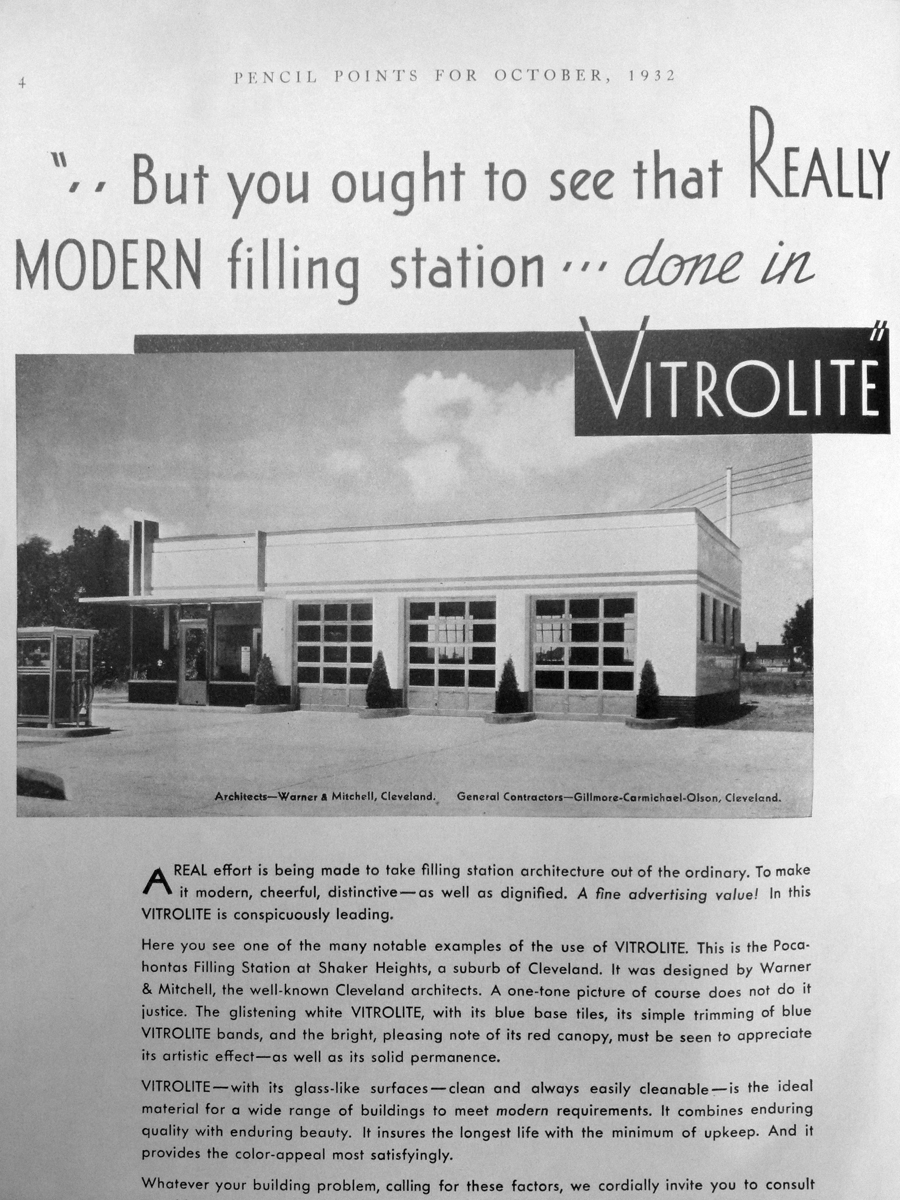

The difference between the magazine’s buildings featured in the advertisements and those in the articles illustrates clearly a profession that was reluctantly posed at a threshold. A modernist design for a “filling station” appears in the advertisement of the Vitrolite Company, a manufacturer of steel enameled panels, promoting their product as “modern, cheerful, distinctive – as well as dignified”. Republic Steel claimed a multitude of applications for their ENDURO stainless steel including a curtain wall on the Yonkers Statesman Building. But this luminal moment is not reflected in the articles; the writers were rooted in a comfortable upper middle class profession looking backward to historic European examples, using exquisite draftsmanship to create designs for a world that was fast disappearing.

The advertisements also reflect a technical and practical aspect of the profession that has disappeared at least from current architectural journals. Along with advertisements for the tools of the trade – such as Higgins drafting inks, Esterbrook pens and the Sketch Book Atelier – there were ads for rigid conduit from General Electric, wire fabric for concrete floor reinforcing and cast iron pipe from Youngstown Steel. The architects of the 1930’s had not relinquished as much of the control of building systems to the engineers as the professionals do today.

Being ‘A Journal for the Drafting Room’, the October 1932 issue also has a detailed and lengthy article on the “Whys and Wherefores of the Specification – Plastering” part of a monthly series of technical specifications. Unlike the “Continuing Education” articles in today’s ‘Architectural Record’, this article was a serious effort to educate. It presupposes a considerable level of professional technical knowledge.

So what are we left with? Where are we when compared with our predecessors of seventy years ago? We have a profession deeply damaged by a severe economic downturn. We have a segment of the community deeply distracted by buildings which have ignored at least some of the Vitruvian rules of fermatas, utilities, venustas. Many critics ignore discussions of process, function, aesthetics and the placement of a building within a context. We have a profession less in control of the construction process and in danger of being relegated to the role of designer rather than master builder.

However, it seems we freely recognize these short comings. During these bad times architects have the opportunity to rethink their roles and redefine where their greatest opportunities and strengths lie. ‘Pencil Points’ of the 1930’s and indeed the ‘Architectural Record’ of 2011 do not reflect the fact that the construction industry, and in fact all of civil society, has a great need for people who care deeply about the shape and form of our built and natural surroundings.