Then And Again

By Andrew Wright

Thanks to a Siren call at a flea market, I recently found myself with several dozen issues of ‘Pencil Points, A Journal of the Drafting Room’ dating from the nineteen thirties and forties. ‘Pencil Points’, as its subtitle indicates, focused on the toilers of the architectural firms. Its readers had aspirations no higher than the drafting room. They wore green eye visors, celluloid cuffs and cotton jackets. Along with Microtomic Van Dyke drawing pencils, this group – for whom drafting was their true job description – has largely disappeared, to be replaced by graduates of architectural school who hope to quickly work their way out of the title. ‘Pencil Points’ also has disappeared. It merged with ‘Progressive Architecture’ in the mid forties, and with the merge, the magazine gradually lost its drafting room orientation. ‘Progressive Architecture’ became the most influential of the “glossy” main stream architectural magazines but ceased publication in December 1995.

Both the articles and the advertisements of these early issues are interesting as paleographic markers defining the state of the profession in the 1930s and illustrating the evolution of our field in the intervening seven decades.

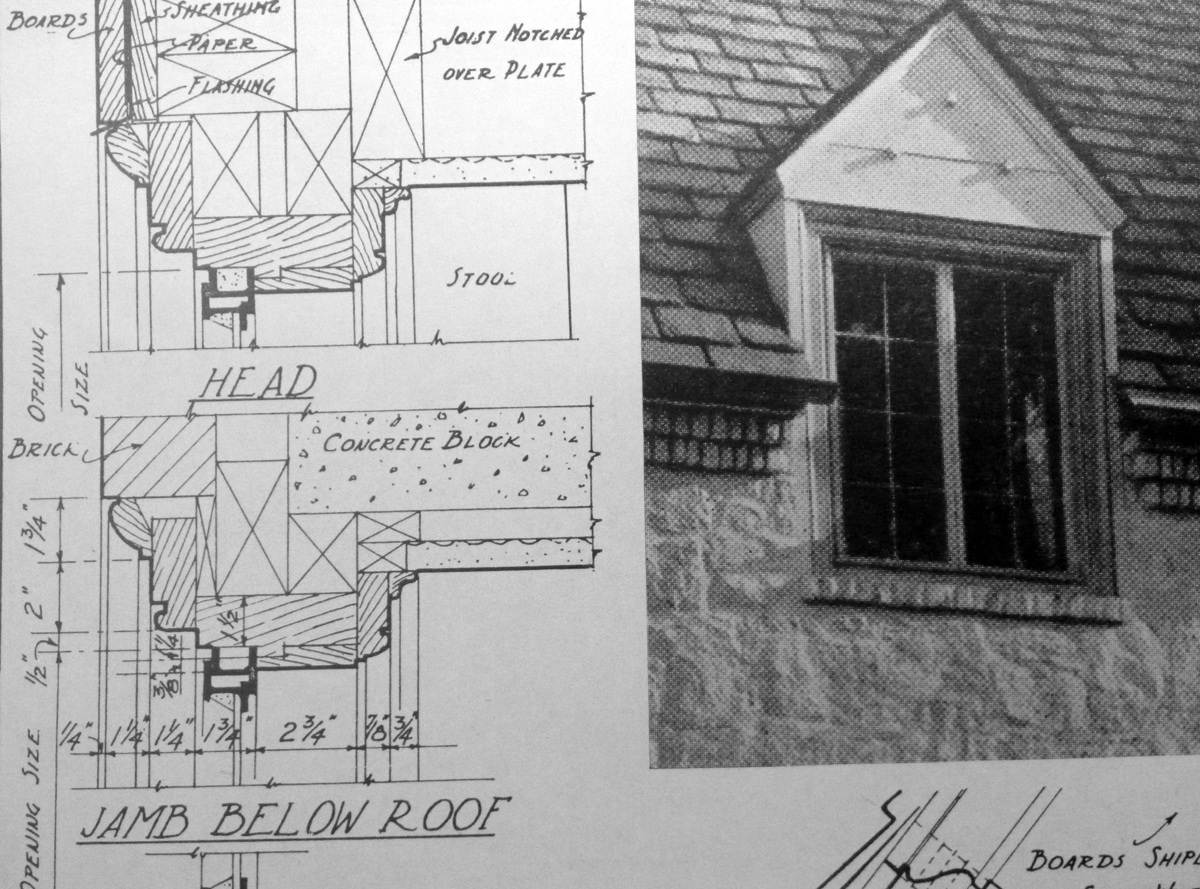

The articles in the issues from the early 1930’s do not directly acknowledge the economic maelstrom that the profession was facing. The lead-off article of the October 1932 issue was entitled “Architecture, Art or Science?” The author, Louis La Baume, grappled with the role of art and science in architecture and wisely decided that this role could not be defined in words. This article was followed by an illustrated monograph on “Early Interior Doorways of New England” and another illustrating the comparative details of dormers in traditional residences.

Though not stated, the profession’s turmoil can be inferred. The exquisitely drafted dormer drawings were prepared by the “New York Architects’ Emergency Unemployment Committee”, whose descendent seems to be the “Not Business as Usual” committee of the New York City Chapter of the AIA formed in December 2008. The NBAU web site makes clear the challenges the profession faces: “The economic downturn has had a significant effect on the design community in New York City. The NBAU program focuses on what design professionals need to know and do for themselves and their firms to thrive”.

Another example of the hard times in the 1930s is the employment listings at the back of the October 1932 issue. There are no listings for help wanted. The ads for the positions wanted include such plaintive supplications as “Willing to take any position and salary offered” and “will work for $35.00 per week anywhere”. These sound agonizingly familiar to anyone looking for work today.

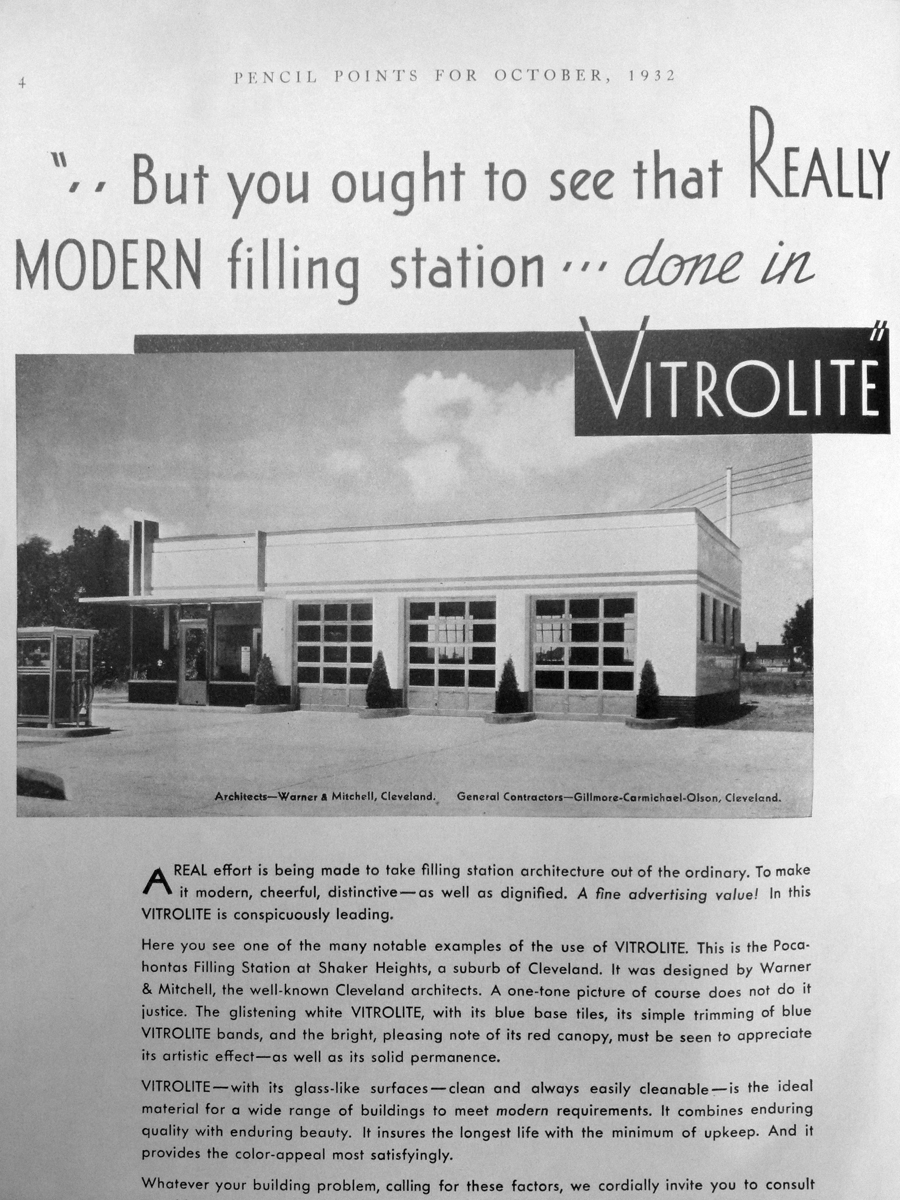

The difference between the magazine’s buildings featured in the advertisements and those in the articles illustrates clearly a profession that was reluctantly posed at a threshold. A modernist design for a “filling station” appears in the advertisement of the Vitrolite Company, a manufacturer of steel enameled panels, promoting their product as “modern, cheerful, distinctive – as well as dignified”. Republic Steel claimed a multitude of applications for their ENDURO stainless steel including a curtain wall on the Yonkers Statesman Building. But this luminal moment is not reflected in the articles; the writers were rooted in a comfortable upper middle class profession looking backward to historic European examples, using exquisite draftsmanship to create designs for a world that was fast disappearing.

The advertisements also reflect a technical and practical aspect of the profession that has disappeared at least from current architectural journals. Along with advertisements for the tools of the trade – such as Higgins drafting inks, Esterbrook pens and the Sketch Book Atelier – there were ads for rigid conduit from General Electric, wire fabric for concrete floor reinforcing and cast iron pipe from Youngstown Steel. The architects of the 1930’s had not relinquished as much of the control of building systems to the engineers as the professionals do today.

Being ‘A Journal for the Drafting Room’, the October 1932 issue also has a detailed and lengthy article on the “Whys and Wherefores of the Specification – Plastering” part of a monthly series of technical specifications. Unlike the “Continuing Education” articles in today’s ‘Architectural Record’, this article was a serious effort to educate. It presupposes a considerable level of professional technical knowledge.

So what are we left with? Where are we when compared with our predecessors of seventy years ago? We have a profession deeply damaged by a severe economic downturn. We have a segment of the community deeply distracted by buildings which have ignored at least some of the Vitruvian rules of fermatas, utilities, venustas. Many critics ignore discussions of process, function, aesthetics and the placement of a building within a context. We have a profession less in control of the construction process and in danger of being relegated to the role of designer rather than master builder.

However, it seems we freely recognize these short comings. During these bad times architects have the opportunity to rethink their roles and redefine where their greatest opportunities and strengths lie. ‘Pencil Points’ of the 1930’s and indeed the ‘Architectural Record’ of 2011 do not reflect the fact that the construction industry, and in fact all of civil society, has a great need for people who care deeply about the shape and form of our built and natural surroundings.