Sleeping Beauty

La Belle au Bois dormant

By Andrew Wright

On a recent trip to Paris I had the opportunity to tour La Maison de Verre with its curator, Mary Johnson, and Raymund Ryan, the curator of the Heinz Architectural Collection of the Carnegie Museum of Art. As a visual experience alone the building far exceeded my expectations. My understanding was increased by my tour companions’ knowledge of the construction process in Paris in the 1930s, and of how its subsequent history has added layers of meaning to the building.

La Maison de Verre has a special niche in the galaxy of modernist architectural design. Despite, or perhaps because of, the building’s relative obscurity, the photographs of its glass block wall suspended above a cour intérieure and its inverse, the double height grand salon, have iconic status in of 20th century architectural history. Beyond these images, however, the building has not been scrutinized to the extent that other designs of this nascent period of modernism have been subjected. Its designers, Pierre Chareau, an “ensemblier”, Bernard Bijvoet, an architect and Louis Dalbert a metal fabricator, are not common place names in any architectural pantheon.

Paris in the thirties was of course a center of ferment for modernism development. La Maison de Verre’s designers were fully aware of aesthetic and polemic concerns for this new style. During its construction Le Corbusier is said to have stopped by to monitor its progress. Upon its completion in 1932 L’Architecture d’Aujound’Hui published a lengthy article.

But subsequently the building seems to have fallen into a certain obscurity. The owners, Anne and Jean Dalsace, maintained the building as a private residence and Dr. Dalsaces’ medical offices. They shrouded the building in a veil of privacy that precluded the merely curious from penetrating the interior court. Many admirers would have to be satisfied with photographs.

Yet the building was not only a private residence; it was also a center of a lively intellectual community. For nearly the forty years the Dalsaces hosted a salon for progressive leftist thinkers. However, this community does not appear to have included the gatekeepers and champions of the new academic architectural style, Modernism. I believe that the designers of la Maison de Verre responded to issues outside of the central concerns of modernism, and in part for this reason the building was passed over.

It was in the late 1960’s, when the first cracks in the façade of modernism began to appear that interest in the building seems to have been rekindled. Kenneth Frampton’s article in Perspecta 12 (1969) reacquainted the English speaking cognoscenti with the building. Dominque Vellay’s La Maison de Verre (2007) is an insightful and personal recollection by the granddaughter of the original owners. She describes eloquently her family’s relationship to their house. François Halard’s photographs provide another hauntingly thoughtful dimension to this book. After Robert Rubin, an American architectural historian and theorist, purchased the building and opened it to historians and architects on a limited basis, it has received more attention, including an article by Nicholai Ourousoff in the New York Times in August 2007.

My observations and thoughts here are those of an architect trained in modernism’s orthodoxy at the end of its reign. I am not a theorist, nor a historian. To quote Woody Guthrie, “I write what I see”. My interpretation is based on a visual reading of the building. Having spent much of my career designing for existing buildings, I am intrigued by the process of understanding and interpreting original design intents and the understanding of the mechanics of construction. La Maison de Verre offers much to consider in these areas.

First the building incorporates elements infrequently found in modernist designs. First, this building reflects the contribution of three individuals trained in related, but distinct, fields. This is a collaborative effort, not a creation of an Ayn Rand styled genius. Who inspired and who developed the designs of the doors with their oval profile, their unique ergonomic hardware and their integrated relation to the movement with the space? With my limited knowledge of Chareau, Bijvoet and Dalbert I could not determine who was leading in the dance at any given moment.

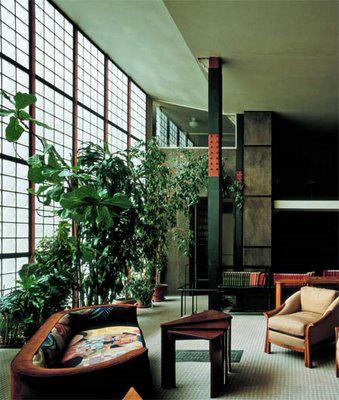

This building is truly a dance. The relationship and movement between the spaces was carefully choreographed by the designers. Unlike the linear progression of the Beaux Art or the directionality of Modernism, there is an intriguing assemblage of materials and spaces. The two story salon is the airy cave that all the other spaces defer to. But beyond that the building is like a wooden toy composed of interlocking shapes fitting neatly into a cube. Each space is carefully considered as a distinct set element accommodating its user, and with an intriguing relation to the greater whole. This interplay between the spaces incorporates visual connections so that the spaces are only semi-permeable. Mr. Ourousoff writes of his realization that the spaces encourage the occupants to orbit around each other. Ms. Velley describes her childhood experience of spying on the adult events in the grand salon from the balcony through the perforated metal screens.

A third modernism edict, a rational structural system organizing the spaces within, is certainly more honored in the breach than the observance in many early modernist designs. In La Maison de Verre this is certainly true. The predicament of inserting the building underneath an occupied apartment may have precluded any attempts to develop such a structural device. I see, however, an overwhelming emphasis on non spacial materiality obscuring any concerns with structural integrity.

The materiality is expressed in stark expressive solutions to utilitarian items such as electrical power outlets, window operators and heating systems and elaborative crafted elements such as stairs and doors. As Ms. Johnson pointed out, this house, like many modernist masterpieces, is an example of hand crafted construction in a machined aesthetic. Some of the materials, such as the “Pirelli” tile flooring, are “out of the box” industrial age products. Other materials, such as the perforated metal screens and the elliptical profiled interior doors, have an industrial imprinteur, but are fabricated with details directly descended from an earlier hand crafted tradition. Others, like the glass block façade, stretch industrial materials to a new aesthetic. There are no “off the shelf” details, but completely thoughtful functional and aesthetic decisions requiring a crafted industrialism. As Mr. Ryan pointed out, the interior displayed the concerns of an interior designer as much as an architect’s.

So what does this building represent in the line of Modernist design? Is it an evolutionary line that did not survive the forces of modernist “rationalism? If it is a road not taken, what can we learn from it and apply to current thought? It is imbued with the many of the concerns of early modernists, for sanitation, for contemporary materials, for new interpretations of building elements. But for me more than any other building of its period it gives a new interpretation of the acts of family life. Chareau considered deeply how people and his building would interact and La Maison de Verre reflects a thoughtful, skilful, intentional design process that intrigued me as did Le Corbusier 60 year ago. This is a building that truly is something before it was about something.