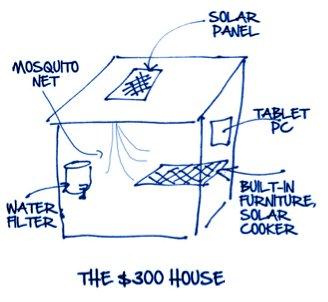

Hypothesis [$300 = House]

Challenges of Housing Production for the Poorest in the Developing World

Report on the 300 Dollar House Workshop, January 25-28 2012 at Dartmouth College

“The Three Hundred Dollar House, you mean three hundred per square foot?” A friend’s incredulity summarizes the responses I heard to the title of a workshop at Dartmouth College. He and I worked together on a project costing multiples of 300 dollars per square foot, his career is in construction, and he knows the price of a pound of nails. The thought of building a house for $300, even at the most minimal standards, seemed an impossibility.

The initial idea of the THDH* was the brain child of Vijay Govindarajan, a professor at the Tuck School of Management at Dartmouth College and Christian Sarkar, referred to as the disruptive fellow in the back. They conceived of the “brand” to bring attention to the issues of housing for the very poorest in the developing world. By provocatively setting the price that low they hoped to push architects, engineers, planners and financiers to explore innovative designs and economic models. They organized an online international competition to initiate the process. Coincidentally the competition drew 300 hundred entries.

From these entries a jury selected six finalists. Many of the finalists were able to attend a workshop hosted by Dartmouth in Hanover in January 2012. The workshop’s goals were to capture the energy sparked by the competition and to explore the steps necessary to create something that would cast a shadow. The workshop, organized by Jack Wilson of the Studio Arts Department, focused on Haiti because of Dartmouth’s connections to the country and its pressing needs.

In addition to the finalists, Dartmouth students and faculty from the engineering and business school, participants from Haitian groups and a handful of engineers and architect were invited. I was included because of my familiarity with designing and building in Haiti. For three intense days the participants wrestled with the issues of urban and rural housing, community development and financial models.

Two Haitian communities, one rural and one urban, were the focus for the workshop. Strong organizations within both communities had originally provided medical services and then branched into social services. Fond des Blancs, a stable rural community relatively untouched by the January 2010 earthquake, benefited from the St. Boniface Haiti Foundation. Cite de Dieu is an urban “slum” in Port-au-Prince. After the earthquake GHESKIO Center, a nearby clinic, filled a vacuum left by a weak and overwhelmed city government by providing not only community medical services but also other significant municipal functions.

During the workshop it fell to me to wear an unfamiliar hat. Instead of my architect’s role Jack asked me to lead the group on community development and infrastructure. We were charged with addressing eight areas:

- Energy Communications

- Transportation

- Potable water

- Sanitation

- Waste Management

- Employment

This formidable list was initially an obstacle. We could not find the key to unlock the process of thinking about the issues of Fond des Blancs and Cite de Dieu. We had too many avenues and too little time and data. It was Jean St Denis, a community organizer from Fond des Blancs, who set us on the right track. He gently repeated until we listened “employment is the key”. He pointed out that even if it was possible to build a three hundred dollar house it still had no viability unless a person could afford it.

Cite de Dieux, Photo

With that insight we looked closely at the issues that inhibited the economic and employment picture of Font des Blancs. We acknowledged that as an island nation with minimal natural resources Haiti’s economic base will eventually lie in exporting their unique products overseas, but assuming that walking must come before running we decided to focus on the local market in town. A list of items available there was developed. The question was raised why there was no fish available at the market even though the town was only 20 kilometers from a coastal fishing village. Jean St. Denis concluded that the issues were not so much physically imposed as the result of culture and customs. He promised to return to Fond des Blancs and institute a motor bike delivery service for fresh fish preserved in ice.

We recognized that many of the issues of poor employment options were not so easily addressed and that it was presumptuous of us to propose solutions from Hanover for Haiti. The general consensus of the workshop participants living in Haiti was that the issue was not a lack of financial resources. There are non-governmental organizations and international governmental agencies looking for viable projects to support and fund. Haitian groups with plans and community backing were in demand. To help Fond des Blancs gain visibility we suggested that a formation of a community development council was a start. The council of the leaders and change agents of the community would analyze in a more thoughtful and through way the steps that we had started.

To that end we created a Facebook page Fond des Blancs as a simple step to help increase the visibility of the community. Please feel free to add your comments there.

Unfortunately we were forced to leave the issues of Cite de Dieu for another time or another group. Besides not having enough time we realized that the urban context had different circumstances. In particularly it is a more fluid and open system.

So if you have read this far and you still do not have the answer to the question “can you build a house for 300 dollars”, the answer is no, at least not in Haiti at the present moment. There does not seem to be a silver bullet for the issues of housing costs, much less the expensive infrastructure. Industrial housing solution is effective in areas with good transportation access and high site labor costs. Lowered costs generally only apply when the scale of production is hundreds, not tens, such as in Levittown, NY after WWII. Traditional materials and forms frequently effectively meet the needs of people who for financial reasons must build their housing in stages. Framing systems which over time may prove more cost-effective, but their introduction into the Haitian market is at a nascent stage.

Immediately after the earthquake there was a plethora of proposals for inexpensive relief housing from designers, architects and engineers of the developed world. Many of these proposals had little relation to Haitian needs and housing expectations, nor to the climate and construction realities of the country. Thankfully most proposals did not get beyond the talking stage.

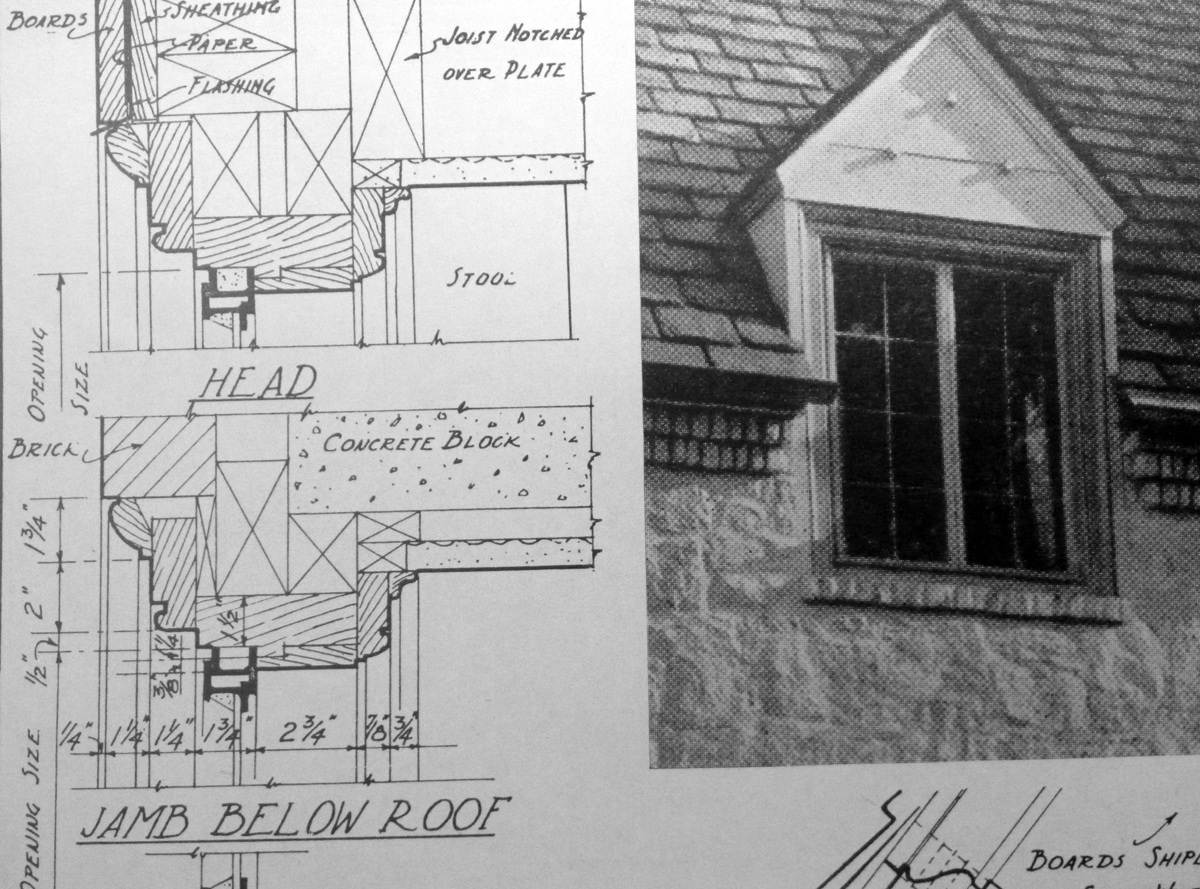

At the Dartmouth workshop the two (rural & urban) housing groups had members who understood the issues relevant to Haiti much more clearly. The groups developed designs based on habitable standards and traditional materials and layout. They responded to the difficulties of building in Cite de Dieu, with the existing poor soil conditions and flooding. In Fond des Blancs the traditional form of front porch, sleeping quarters and rear yard for cooking were respected.

However, in both locations the costs were in the thousands of dollars, not in the hundreds – even when pared down to the “basic starter unit”. So if the number was wrong, does that invalidate the process? Without that number or another like it, the workshop would not have gotten off the ground. If you can harness the energy of the workshop into a prototype, if a student’s career takes on an added dimension, if the arrival of fresh fish in Fond des Blancs triggers the birth of a stronger market, then the workshop was a success.