Building Reenactment: Defining the Past

Mark Twain wrote:

“I have no special regard for Satan; but I can at least claim I have no prejudice against him. It may even be that I lean a little his way, on account of his not having a fair show. All religions issue bibles against him, and say the most injurious things about him, but we never hear his side. We have none of the evidence for the prosecution, and yet we render the verdict. To my mind, this is irregular. It is un-English: it is un-American; it is French…of course Satan has some kind of a case, it goes without saying. It may be a poor one, but that is nothing; that can be said about any of us.”

I am not going to come to the defense of Satan, or comment on Mark Twain’s opinions of the French, but I want you to suspend your preconceptions for a moment and consider with me that stepchild of the preservation movement, architectural reconstruction. It is my destiny to make this argument, since for the last six years I have been deeply involved in the reconstruction of a French Military Building, the Mars Education Center ( le Magazin du Roi) at Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain in New York State. I want to engage you in a making a case for architectural reconstruction within a historic site.

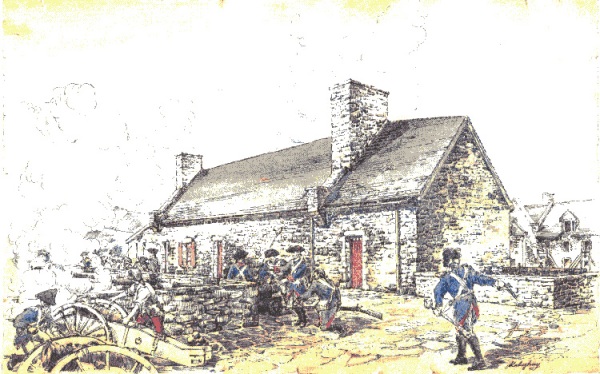

Allow me to set the stage: The Ticonderoga peninsula on Lake Champlain, NY, has many stories to tell, but for North Americans, the role it played in the Seven Years War and Revolutionary War dominates. In 1755, the French, realizing the site’s importance for their control of Lake Champlain, began constructing Fort Carillion on the peninsula’s high ground. After four years of labor by thousands of soldiers and artisans, the French were forced to abandon the fort by the attacking British, but not before exploding its gunpowder magazine. The British took the fort, renamed it Ticonderoga, made some basic repairs, and lightly garrisoned it. However, the fort lost its military significance even before the end of the Revolutionary War, and the harsh Adirondack winters proved the ephemeral nature of European building techniques in a freeze thaw climate. The fort was fast becoming a picturesque ruin.

Financier William Ferris Pell eventually rescued the fort from further destruction and, early in the 20th century, in one of our nation’s earliest preservation efforts, Pell family members initiated the fort’s restoration, opening it in 1909 as the country’s first open-air museum. Since that time, through its buildings, collections and programs, the fort has instilled in its visitors a sense of the history and culture of this mythic place. The site was always interpreted physically as a British/American fort, and the east side – the French gunpowder magazine – was never restored.

Reconstruction & Honesty

The tension between reconstruction and honesty was evident early on. In 1846 at the inception of the awareness of the issues inherent in reconstruction and restoration, John Ruskin wrote in the Seven Lamps of Architecture: “It is impossible, as impossible as to raise the dead, to restore anything that has ever been great or beautiful in architecture.” The difficulties of “raising the dead” have been well documented in the ensuing 150 years. The goal of historic accuracy has become enmeshed with present concerns on countless projects.

This was codified in the Athens Charter of 1931. There the preservation and architectural communities set out to proscribe the popular restoration/reconstruction epitomized by the work of Viollet-le-Duc, and these popular American open-air museums. The professional approach became one of respecting all previous intervention, and encouraging a view of old buildings as historical documents. Viewed as such, ‘historic’ buildings could be studied and admired but never copied. The honesty of structure that le-Duc saw in Medieval structures had been transformed into an honesty of visual intention and a concern of falsifying history.

A Means of Education

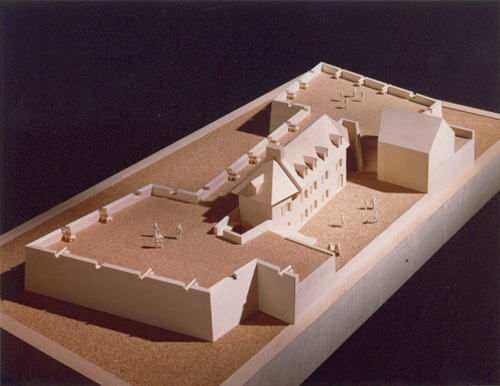

In the spring of 2000, the Fort Ticonderoga Association brought my firm on board to develop the program and schematic designs for the reconstruction of the East Barracks. We were aware that the re-creation of this 18th century building from the available sources presented an ethical and technical dilemma; We have little direct physical evidence about the building’s configuration or tectonics and no existing immediate prototypes.

The decision to attempt a French, rather than an English reconstruction, came to members of the team, professional consultants and Fort staff alike. We realized that we should be designing a French building portraying as accurately as we know the exterior appearance of its progenitor, while simultaneously accommodating a 21st century building program and the systems that support it. The exterior of the building is as authentic a reconstruction as we know how to do in the early 21st century, based on our research while the interior is an unabashedly modern building.

![]()

Responsible historic reconstruction is, in part, defining the past – within admittedly artificial time constructs – and accepting our role as stewards. If historic places represent our ancestors – and they do – treatments shouldn’t be undertaken at their expense. It is appropriate to reconstruct when it deepens our understanding of the past; when in the process one does not destroy resources or artifacts that are currently telling their own story. Reconstruction should always be as honest and respectful as possible toward people from the past, the built environment, and time. We construct artifacts to give meaning to our lives. An architectural reconstruction is such an artifact, and it empowers the interpretation of history to create deep and abiding meanings.

Mine is not an argument for revisiting architectural classicism, new urbanism, and certainly not the silliness of post modernism. I am talking about reconstruction within the context of an historic site with the intention to educate. I acknowledge that reconstruction will open the door to human error in decision-making. The concepts of the current designer, the proposed program, and the contemporary technology create an illusion that illustrates the reconstructor’s vision of history. But if we don’t attempt to reconstruct we have lost an opportunity to expand our understanding of the past. In this context effort of reconstruction matters because it lasts and it is a tangible means of explaining the historical record.